Web designers provide the framework for content. Then it’s up to others to provide the content. Pictures, videos, text, colour, readability are important for accessibility once the site is built.

Web designers provide the framework for content. Then it’s up to others to provide the content. Pictures, videos, text, colour, readability are important for accessibility once the site is built.

The UK Government has a series of six digital design posters for designers. The aim is to raise awareness of people with different digital access needs. To keep things simple, the posters are divided into Do and Don’t. The content of each poster is listed on the webpage titled, The Dos and Don’ts on designing for accessibility. Also available in 17 languages.

The posters help designers make online services accessible. They cover low vision, deaf and hard of hearing, dyslexia, motor disabilities, people with autism and users of screen readers.

The posters are simple and this is what makes them effective. Basically they act as visual prompts to designers rather than offering technical know-how. There are posters for people:

who are Deaf or hard of hearing

with physical or motor disabilities.

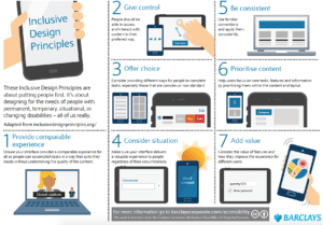

Posters by Barclays Bank

Barclays Bank has developed a set of inclusive digital design posters. They are based on seven design principles. These principles can be applied to other design fields as well as digital platforms. You can download the A3 poster which gives a quick overview. Or download a more detailed set of A4 posters.

The posters are a good quick reference for web and app design professionals. The seven principles below are explained in more detail: More detail of the seven principles are explained:

-

-

- Provide comparable experience

- Consider situation

- Provide comparable experience

- Be consistent

- Give control

- Offer choice

- Prioritise content

- Add value

-

Artificial Intelligence and inclusion

The way businesses design and develop new technology will determine the inclusiveness of our digital society. Technology has the potential to bring people with disability into the workforce.

The 24 page PDF report, Amplify You, covers understanding the digital divide, design for humans, AI is the new UI, and more. I the last section, What to Do Now, it has bullet points under headings of: Understand the implications of accessibility, Design accessibility into your business, Build an ecosystem of accessibility – and continuously think about what is next.

When you are in a rush it’s easy to leave out the description of the image in the alt-text box – but should you?. Alt-text is a description of an image that’s shown to people, who for some reason, can’t see the image. Among other things, alt-texts help:

When you are in a rush it’s easy to leave out the description of the image in the alt-text box – but should you?. Alt-text is a description of an image that’s shown to people, who for some reason, can’t see the image. Among other things, alt-texts help: Colour vision deficiency or colour blindness affects around 10 per cent of the population. But each person varies in what colours they can see, which is why it is not “colour blindness”. So what colours are best if you want all readers to enjoy colours on your website?

Colour vision deficiency or colour blindness affects around 10 per cent of the population. But each person varies in what colours they can see, which is why it is not “colour blindness”. So what colours are best if you want all readers to enjoy colours on your website? It’s one thing to talk about colour blindness, but it is quite another to see what it looks like to the 6-10 per cent of the population that have colour vision deficiency.

It’s one thing to talk about colour blindness, but it is quite another to see what it looks like to the 6-10 per cent of the population that have colour vision deficiency.

When choosing a web developer to update your site, don’t assume they know all about accessibility. The guidelines for web accessibility are often treated like tacked on ramps to a building. That is, something you think of after you’ve done the design. To ensure accessibility of your site, it pays to know how web design decisions are made. And you don’t need to be a tech person.

When choosing a web developer to update your site, don’t assume they know all about accessibility. The guidelines for web accessibility are often treated like tacked on ramps to a building. That is, something you think of after you’ve done the design. To ensure accessibility of your site, it pays to know how web design decisions are made. And you don’t need to be a tech person. The Centre for Excellence in Universal Design in Ireland has a comprehensive

The Centre for Excellence in Universal Design in Ireland has a comprehensive The ability to access online content provides access to goods and services, and in COVID times, each other. But content on websites and smart phones is not user-friendly for everyone, particularly people with cognitive disability. However, digital communication is here to stay and it needs to be inclusive.

The ability to access online content provides access to goods and services, and in COVID times, each other. But content on websites and smart phones is not user-friendly for everyone, particularly people with cognitive disability. However, digital communication is here to stay and it needs to be inclusive.  The inventors of Zoom could not have predicted the level of use during COVID lockdowns. It is one of the easiest to use and one reason it is popular with business and families. It also has provision for live captioning for people who have difficulty hearing. However, the purpose of video platforms is to see who you are talking to. But what if they are a fuzzy block of faces? Here are some tips on Zoom for people with vision loss.

The inventors of Zoom could not have predicted the level of use during COVID lockdowns. It is one of the easiest to use and one reason it is popular with business and families. It also has provision for live captioning for people who have difficulty hearing. However, the purpose of video platforms is to see who you are talking to. But what if they are a fuzzy block of faces? Here are some tips on Zoom for people with vision loss.  When a government department or access committee starts talking about access maps and map accessibility, where do you start? Of course there are consultants to help with this, but it’s good to have some idea of what to put in the brief. It’s also a good idea to know if the right thing has been delivered. A toolkit or guide for maps would be great but there’s a little to be found in lay language.

When a government department or access committee starts talking about access maps and map accessibility, where do you start? Of course there are consultants to help with this, but it’s good to have some idea of what to put in the brief. It’s also a good idea to know if the right thing has been delivered. A toolkit or guide for maps would be great but there’s a little to be found in lay language.

Would academic coaching help post secondary students with disabilities achieve their education goals? That was the question for a pilot study. Not surprisingly, the coaching helped. Improved self esteem and confidence helped the students achieve degrees in STEM subjects. The key component of academic coaching for students was helping students with their executive functioning.

Would academic coaching help post secondary students with disabilities achieve their education goals? That was the question for a pilot study. Not surprisingly, the coaching helped. Improved self esteem and confidence helped the students achieve degrees in STEM subjects. The key component of academic coaching for students was helping students with their executive functioning.