Empathy driven design is a catalyst for social change. It challenges architects to consider the broader impact of their designs on social equity to make spaces more inclusive. By integrating empathy into the design process, architects can create more equitable, caring environments that serve the common good. Despite the challenges, empathy driven design is a paradigm shift in architecture, moving away from top-down, one-size-fits-all solutions.

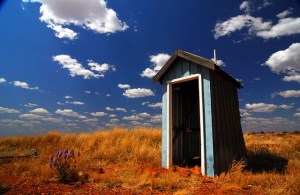

Empathy driven design is based on collaboration. That is, engaging with communities to understand their unique experiences and challenges. The architect becomes a listener and participant in the co-design process. Image courtesy of MASS Design Group from ArchDaily.

An article in ArchDaily explains more about designing with empathy and for social equity. Examples of empathy driven design include, among others, a hospital in Rwanda and a housing project in Chile. Projects in developed countries require the same thought as these examples and show what’s possible.

Challenges and opportunities

One of the most significant hurdles is balancing empathy with practical constraints such as budget, time, and regulatory limitations. Many projects that aim to serve disadvantaged communities are often restricted by tight budgets.

The key issue is the cost of time and project deadlines. Navigating this tension requires creative solutions that make the most of available resources without compromising the project’s empathetic core.

Design alone cannot overcome deeply entrenched societal inequalities. The success of designs depend on both the built environment and broader support systems, such as social services or public policy changes.

The title of the article is, Designing with Empathy: Architecture for Social Equity.

Empathy: the key to inclusive design

Loughborough University has a good track record for inclusive design research. Low vision and manual dexterity are the most common losses for people as they age. Consequently, the study focused on these factors to improve architects’ empathy and understanding of users.

The method involved using glasses and gloves that simulate loss of vision and loss of hand dexterity. Participants wore the glasses and gloves and then given reading, writing and dexterity tasks.

The results show that the tasks challenged their traditional view of disability. Participants began to see it more as a continuum and effecting a wider population.

Key themes

- Inadequacy of the current building standard.

- There is no incentive for developers to go beyond minimum compliance.

- Developers often commission design briefs so the end user is often unknown.

- In the absence of knowing their end user, they tend to design for themselves.

- They feel there is a stigma associated with accessible designs and this reinforces the disability-centric concept of able bodied versus disability designs.

- It challenged their traditional view between ‘able-bodied’ and ‘disabled-users’.

- A lack of inclusive design training within their undergraduate and post graduate training.

- Participants felt strongly that commercial, accessible design decisions, mainly addressed physical impairments.

- All participants reported an increased awareness of the psychological effects of the simulated capability loss, reporting frustration and fatigue.

The title of the article is, How ‘Empathetic modelling’ positively influences Architects’ empathy, informing their Inclusive Design-Thinking. Arthritis affects one in seven Australians. Opening packages, lifting the kettle and turning door knobs can be difficult and painful.

The video below shows the gloves and glasses in action.

Designing for empathy

Human centred design and inclusive design processes focus taking an empathetic approach to the users. But what if you turn that around and think about designing for empathy itself? To shift from being the empathiser to become an empathy generator? That was the question a team of designers in Finland wanted to know the answer to. Using socio-cultural design tools rather than physical empathy design tools, they created a co-creative process with the Finnish parliament.

The title of the paper is, Design for Empathy: A co-design case study with the Finnish Parliament.

From the abstract:

Globalisation and the mixing of people, cultures, religions and languages fuels pressing healthcare, educational, political and other socio-cultural issues. Many issues are driven by society’s struggle to find ways to facilitate more meaningful ways to help overcome the empathy gap which keeps various groups of people apart.

This paper presents a process to design for empathy – as an outcome of design. This extends prior work which typically looks at empathy for design – as a part of the design process, as is common in inclusive design and human centered design process.

We challenge the role of the designer to be more externalised, to shift from an empathiser to become an empathy generator. We develop and demonstrate the process to design for empathy through a co-creation case study aiming to bring empathy into politics.

The Parliament of Finland is the setting for the project. It involves co-creation with six Members of the Parliament from five political parties. We discuss the outcomes of the process including design considerations for future research.

Although Japan has the oldest population in the world, creating accessible urban spaces is making very slow progress.

Although Japan has the oldest population in the world, creating accessible urban spaces is making very slow progress.