Griffith University supported the 4th Australian Universal Design Conference held in Melbourne by publishing full papers and extended abstracts. See the links below for access.

Community-based studios for enhancing students’ awareness of universal design principles. Hing-Wah Chau.

Universal design in housing: Reporting on Australia’s obligations to the UNCRPD. Note: The presentation updated delegates on the latest information about the recent change to the National Construction Code. Margaret Ward (ANUHD) and Hugh Bartram (Victorian Government).

From niche to mainstream: local government and the specialist disability housing sector. Linda Martin-Chew and Rosie Beaumont.

Thriving at School: How interoception is helping children and young people in learning everyday. Emma Goodall (workshop).

Universal Design and Communication Access. Georgia Burn.

Achieving visual contrast in built, transport and information environments for everyone, everywhere, everyday. Penny Galbraith.

Mobility Scooters in the Wild: Users’ Resilience and Innovation. Theresa Harada.

Understanding the Differences between Universal Design and Inclusive Design implementation: The Case of an Indonesian Public Library. Gunawan Tanuwidjaja (Poster).

Accessible Events: A multi-dimensional Approach to Temporary Universal Design. Tina Merk.

Everyone, everywhere, everyday: A case for expanding universal design to public toilets. Katherine Webber.

Reframing Universal Design: Creating Short Videos for Inclusion. Janice Rieger (workshop).

*Designing with the Digital Divide to Design Technology for All. Jenna Mikus.

The papers were launched at the CUDA Transportation webinar in October 2020 by Dr Faith Valencia-Forrester, Griffith University.

*Published May 2021.

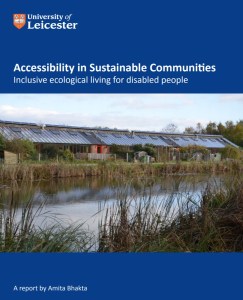

Can homes be both eco-friendly and accessible? If not, it means people with disability and older people are excluded from the benefits of an eco-home. Part M of the UK building regulations require a level threshold and a downstairs toilet. The Lifetime Home standard provides for more flexibility for adaptation. Accessible eco homes are possible with the help of designers

Can homes be both eco-friendly and accessible? If not, it means people with disability and older people are excluded from the benefits of an eco-home. Part M of the UK building regulations require a level threshold and a downstairs toilet. The Lifetime Home standard provides for more flexibility for adaptation. Accessible eco homes are possible with the help of designers  The most well-known guide for ageing populations is the World Health Organization’s

The most well-known guide for ageing populations is the World Health Organization’s

Get up to speed with this

Get up to speed with this Transportation systems are more than buses and bus stops, or trains and stations. They consist of infrastructure, customer service, regulations, and system organisation. Taking a universal design approach is a good way to frame and achieve inclusive mobility systems.

Transportation systems are more than buses and bus stops, or trains and stations. They consist of infrastructure, customer service, regulations, and system organisation. Taking a universal design approach is a good way to frame and achieve inclusive mobility systems.

The international Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disability asked Australia some

The international Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disability asked Australia some  From 2022, all new homes will be built to Silver level of the

From 2022, all new homes will be built to Silver level of the

Retirement living has to factor pandemics into design now. Separation rather than isolation is the key. Much of the value of specialist retirement living is the easy access to amenities and socialisation. But the pandemic put a stop to both. The constant reminder that older people are more vulnerable to the infection was the last straw. Especially as everyone fell into the vulnerable category. Consequently, everyone got isolated from each other. But how to design for this?

Retirement living has to factor pandemics into design now. Separation rather than isolation is the key. Much of the value of specialist retirement living is the easy access to amenities and socialisation. But the pandemic put a stop to both. The constant reminder that older people are more vulnerable to the infection was the last straw. Especially as everyone fell into the vulnerable category. Consequently, everyone got isolated from each other. But how to design for this?