Ageing is ordinary – everyone is doing it. But somehow it’s thought of as an older person’s state of being. Policies, buildings, places, and products have a side-bar for older people. These side-bars are separate special policies, places to live, places to go and things to use. However, older adults want ordinary designs that work for them as well as others. It’s what gives a sense of inclusion and belonging. This segregation and stereotyping is not good for health. What older adults need is more universal design.

Ageing is ordinary – everyone is doing it. But somehow it’s thought of as an older person’s state of being. Policies, buildings, places, and products have a side-bar for older people. These side-bars are separate special policies, places to live, places to go and things to use. However, older adults want ordinary designs that work for them as well as others. It’s what gives a sense of inclusion and belonging. This segregation and stereotyping is not good for health. What older adults need is more universal design.

Peter Snyder is an advocate for universal design across products, services and built environment. In his article he explains the impact of “specialness” on the health and well-being of older adults. Stereotyping is particularly damaging. Some stereotypes are obviously not true, such as older people can’t deal with technology. But that doesn’t stop people from perpetuating them and that includes older people themselves.

When older people complete a memory test after reading that older people have impaired memory function, they perform more poorly than those who didn’t read the material. And the reverse is true. A positive statement brought about an improvement in the memory test. Snyder adds that if cognitive decline was a basic human trait, it would be seen across all cultures. However, this is not the case.

Snyder’s article argues that our beliefs about the ageing process have a significant impact on our wellbeing in later life.

The role of designers

If and when we need a product to help with a daily task, why does it need to be a special one? And why does it have to be purely functional with no aesthetics considered in the design? Too many functional products are clunky and ugly. It’s why people shun such products such as walking canes and mobility devices. It’s depressing.

By definition, stereotypes are rarely, if ever, true – even positive ones. But used as positive feedback it can work. But not by citing such things as “older people are wiser”. It is done by creating services and products that are inclusive so that age becomes irrelevant. This is why older people need universal design.

A good article showing the unintended consequences of ageist stereotypes on health and wellbeing and what designers can do about it. The title is, Universal Design as a Paradigm for Providing Health Interventions for Older Adults.

Disability rights, accessibility and inclusion have come a long way. But we are not there yet. It’s taken more than 50 years to get to this point. That’s despite legislation, public policy statements, and access standards. Ableism and ableist attitudes are alive and well. Yet many people aren’t aware of how this undermines inclusion and equitable treatment. The same goes for ageism.

Disability rights, accessibility and inclusion have come a long way. But we are not there yet. It’s taken more than 50 years to get to this point. That’s despite legislation, public policy statements, and access standards. Ableism and ableist attitudes are alive and well. Yet many people aren’t aware of how this undermines inclusion and equitable treatment. The same goes for ageism.  Overcoming ableism takes more than attending a disability awareness workshop. It’s also more than checking out the right words to use when talking about disability. If things are to change for people with disability, we have to challenge values and assumptions.

Overcoming ableism takes more than attending a disability awareness workshop. It’s also more than checking out the right words to use when talking about disability. If things are to change for people with disability, we have to challenge values and assumptions.  It’s not just the buildings or landscaping that make cities – the spaces in between matter too. These is where the social aspect sits. Blue and green infrastructure and public art are important factors and it’s universal design that joins the dots for urban design.

It’s not just the buildings or landscaping that make cities – the spaces in between matter too. These is where the social aspect sits. Blue and green infrastructure and public art are important factors and it’s universal design that joins the dots for urban design.

As our populations age we will have more people experiencing low vision. This means that contrasts between objects will become an increasingly important factor in negotiating the built environment.

As our populations age we will have more people experiencing low vision. This means that contrasts between objects will become an increasingly important factor in negotiating the built environment.  The findings and conclusion of the study raise an important question: Are the staircases as bad as they seem in terms of not meeting the legislative requirements? Or are the requirements too difficult to fulfil? The team concluded that the answer lies with a representative group of people with low vision guiding them on understanding usability. Another case of standards being useful but not entirely effective – the users have the answer once again.

The findings and conclusion of the study raise an important question: Are the staircases as bad as they seem in terms of not meeting the legislative requirements? Or are the requirements too difficult to fulfil? The team concluded that the answer lies with a representative group of people with low vision guiding them on understanding usability. Another case of standards being useful but not entirely effective – the users have the answer once again. What is luminance contrast and how do you measure it? The non-technical explanation is the contrast of the light reflected on one surface compared with that of another, adjoining or adjacent surface. For example the contrast between the kitchen bench and the cupboard below and the wall behind.

What is luminance contrast and how do you measure it? The non-technical explanation is the contrast of the light reflected on one surface compared with that of another, adjoining or adjacent surface. For example the contrast between the kitchen bench and the cupboard below and the wall behind.  The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) has an Easy Read guide to the Disability Strategy 2021-2031. However, you need good reading and web navigation skills to get to it. The information is spaced out over 44 pages in the PDF version.

The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) has an Easy Read guide to the Disability Strategy 2021-2031. However, you need good reading and web navigation skills to get to it. The information is spaced out over 44 pages in the PDF version.  When you are in a rush it’s easy to leave out the description of the image in the alt-text box – but should you?. Alt-text is a description of an image that’s shown to people, who for some reason, can’t see the image. Among other things, alt-texts help:

When you are in a rush it’s easy to leave out the description of the image in the alt-text box – but should you?. Alt-text is a description of an image that’s shown to people, who for some reason, can’t see the image. Among other things, alt-texts help: Colour vision deficiency or colour blindness affects around 10 per cent of the population. But each person varies in what colours they can see, which is why it is not “colour blindness”. So what colours are best if you want all readers to enjoy colours on your website?

Colour vision deficiency or colour blindness affects around 10 per cent of the population. But each person varies in what colours they can see, which is why it is not “colour blindness”. So what colours are best if you want all readers to enjoy colours on your website? It’s one thing to talk about colour blindness, but it is quite another to see what it looks like to the 6-10 per cent of the population that have colour vision deficiency.

It’s one thing to talk about colour blindness, but it is quite another to see what it looks like to the 6-10 per cent of the population that have colour vision deficiency.

Across the globe, advocates for universal design in housing find themselves faced with the same myths. And these myths prevail in spite of hard evidence. AgeUK and Habinteg have put together a fact sheet,

Across the globe, advocates for universal design in housing find themselves faced with the same myths. And these myths prevail in spite of hard evidence. AgeUK and Habinteg have put together a fact sheet,  How can we measure the economic benefits of designing our built environments to ensure access for everyone? Good question. Tourism has a solid body of knowledge on the economics of inclusion, and housing studies cite savings for health budgets. However, we need a benchmark to show clear and direct economic benefits for stakeholders and society. But it has to be meaningful accessibility, not just minimal compliance to standards. That’s the argument in a paper from Canada.

How can we measure the economic benefits of designing our built environments to ensure access for everyone? Good question. Tourism has a solid body of knowledge on the economics of inclusion, and housing studies cite savings for health budgets. However, we need a benchmark to show clear and direct economic benefits for stakeholders and society. But it has to be meaningful accessibility, not just minimal compliance to standards. That’s the argument in a paper from Canada. Universal design is most commonly associated with the built environment. This is where the physical barriers to inclusion are most visible. But the concept of universal design goes beyond this to include cognitive accessibility.

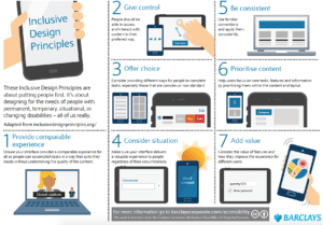

Universal design is most commonly associated with the built environment. This is where the physical barriers to inclusion are most visible. But the concept of universal design goes beyond this to include cognitive accessibility. The working group has published two standards since forming in 2015. The first provides guidelines for the design of products to support daily time management. The second is about the design and development of systems, products, services and built environments. A third standard is under development. This one sets out the requirements for reporting the cognitive accessibility of products and systems.

The working group has published two standards since forming in 2015. The first provides guidelines for the design of products to support daily time management. The second is about the design and development of systems, products, services and built environments. A third standard is under development. This one sets out the requirements for reporting the cognitive accessibility of products and systems.