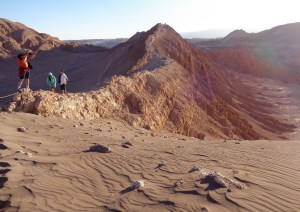

Are ableist views preventing the tourism and recreation sectors from being accessible and inclusive? This is a question arising from a scoping review of policies, practices and infrastructure related to nature-based settings. The review found many barriers were related to operator or designer assumptions about the value of the experience for people with different disabilities. And “accessible nature” is yet to be expressed in the form of access standards.

Assumptions about value such as “this place is about the view, so why would blind people be interested?” is rarely explicitly expressed. Rather, it is embedded in systems and processes that place barriers, albeit inadvertently, to accessibility for all. But other barriers exist such as threats to conservation values that say, a footpath could impose. Consequently, ways to minimise the negative impacts on both social and ecological aspects should be found when introducing built structures.

A more worrying view is that it is not safe for people with disability to experience certain landscapes. This perpetuates organisational notions that people with disability need extra care or special settings. Or that people with disability can’t or don’t experience nature in the same way as non-disabled people.

From the conclusions

In the conclusions, the authors lament, “Perhaps more troublingly, there are indications that such gaps are intertwined in cultures within the tourism and recreation sector that perpetuate ablest views of what should be considered a genuine and laudable way to experience nature.”

The authors conclude there is a pressing need for specific standards for nature-based tourism and recreation spaces. People developing such standards should ensure they are not underpinned by current ableist views.

The health and wellbeing factors of nature contact are well established. So, it’s important for everyone to have easy access to the experiences nature offers.

The title of the scoping review is, Accessible nature beyond city limits – A scoping review. The authors are based in Canada.

Abstract

The health and well-being benefits of nature contact are well known, but inequitably distributed across society. Focusing on the access needs of persons with a disability, the purpose of this study was to systematically examine research on the accessibility of nature-based tourism and recreation spaces outside of urban/community settings.

Following a scoping review methodology, this study sought to examine policies, services, physical infrastructures, and regulatory standards intended to enable equitable use of nature-based settings by individuals of all ages and abilities, particularly persons with a disability.

In total, 41 relevant studies were identified and analyzed. Findings indicate that there are considerable gaps in the provision of services and information that enable self-determination in the use and enjoyment of nature, and that accessibility in nature-based settings is conceptualized through three interrelated policy/design pathways: the adaptation pathway, the accommodation pathway, and the universal design pathway.

As a whole, accessibility policy and standards research specific to natural settings outside of urban/community settings is highly limited.

Management implications

There are growing calls to promote inclusive nature experiences in tourism and recreation spaces outside of community settings. Management of such spaces must reconcile equity concerns with a host of other priorities like environmental conservation.

In the case of promoting universal accessibility, few studies offer insight into the detailed standards that must be met to create barrier-free access, let alone how to integrate such standards with other management priorities.

Transdisciplinary research partnerships that involve management personnel, environmental and public health researchers, and persons with a disability are needed to identify effective management synergies.

Photo by Jane Bringolf

Lookout towers are usually built with steps, so how can you make them accessible? The answer is of course a ramp, but not just any ramp. The Stovner Tower in Oslo shows how you can create a beautiful walkway with universal design. It curves and loops for 260 metres until it reaches 15 metres above ground. This provides excellent views of the city and landscape beyond. Located on the forest edge it is a destination for everyone to enjoy.

Lookout towers are usually built with steps, so how can you make them accessible? The answer is of course a ramp, but not just any ramp. The Stovner Tower in Oslo shows how you can create a beautiful walkway with universal design. It curves and loops for 260 metres until it reaches 15 metres above ground. This provides excellent views of the city and landscape beyond. Located on the forest edge it is a destination for everyone to enjoy. The tower has become a popular destination for both locals and visitors.

The tower has become a popular destination for both locals and visitors.  Visits to heritage sites are more than history and the site itself. It’s also about the interactions you have with others.

Visits to heritage sites are more than history and the site itself. It’s also about the interactions you have with others.  Should we call it ‘inclusive tourism’ or ‘accessible tourism?’ Well that depends. If it is a destination or activity specifically designed for people with disability then it’s accessible. If it is a mainstream service AND it is fully accessible for everyone then it’s inclusive. There is a place for both. However, inclusive in this context is not to be confused with “all inclusive” products and services where the price includes everything.

Should we call it ‘inclusive tourism’ or ‘accessible tourism?’ Well that depends. If it is a destination or activity specifically designed for people with disability then it’s accessible. If it is a mainstream service AND it is fully accessible for everyone then it’s inclusive. There is a place for both. However, inclusive in this context is not to be confused with “all inclusive” products and services where the price includes everything.

A lot has been written about accessible and inclusive tourism. It’s a pity we are still writing. Economic evidence, training packages, and guidelines have made some progress over the years. But we are not there yet. And it gets more complex. We’ve moved on from a ramp for wheelchair access to considering many other disabilities. Here are 3 key changes for hotels and airlines for people with cognitive conditions.

A lot has been written about accessible and inclusive tourism. It’s a pity we are still writing. Economic evidence, training packages, and guidelines have made some progress over the years. But we are not there yet. And it gets more complex. We’ve moved on from a ramp for wheelchair access to considering many other disabilities. Here are 3 key changes for hotels and airlines for people with cognitive conditions. Now that Airbnb has

Now that Airbnb has  Who is the customer of inclusive tourism? Everyone! This is the introduction to the

Who is the customer of inclusive tourism? Everyone! This is the introduction to the  The

The

When the user of a place or thing is most likely to be a person with disability, it is often labelled “disabled”. But what about places being disabled? “Disabled” in it’s original meaning is something that doesn’t work. So, if the chain of accessibility for everyone is missing, the place is indeed disabled. This was pointed out in an article in The Guardian: “

When the user of a place or thing is most likely to be a person with disability, it is often labelled “disabled”. But what about places being disabled? “Disabled” in it’s original meaning is something that doesn’t work. So, if the chain of accessibility for everyone is missing, the place is indeed disabled. This was pointed out in an article in The Guardian: “

“The basic task of accessible tourism is to stop focusing on the features of disability and to concentrate on various social needs and adjusting the conditions of geographical (social and physical) space to them”.

“The basic task of accessible tourism is to stop focusing on the features of disability and to concentrate on various social needs and adjusting the conditions of geographical (social and physical) space to them”.