Justice systems and courthouses are scary at the best of times – even when you haven’t done anything wrong. The processes and places are foreign to most of us. Interacting with the justice system is very stressful – even more so for people with any kind of disability. It’s the same for people who come from a migrant community. Equitable access to justice is yet to evolve.

The newly published guidelines for access to justice for persons with disabilities is available on the United Nations Human Rights web page. It gives the background and a summary of the consultation process. The title of the document is, International Principles and Guidelines on Access to Justice for Persons with Disabilities. The document was developed in collaboration with disability rights experts, advocacy organisations, states, academics and other practitioners. There are ten principles, each with a set of guidelines for action.

Ten Principles

Principle 1 All persons with disabilities have legal capacity and, therefore, no one shall be denied access to justice on the basis of disability.

Principle 2 Facilities and services must be universally accessible to ensure equal access to justice without discrimination of persons with disabilities.

Principle 3 Persons with disabilities, including children with disabilities, have the right to appropriate procedural accommodations.

Principle 4 Persons with disabilities have the right to access legal notices and information in a timely and accessible manner on an equal basis with others.

Principle 5 Persons with disabilities are entitled to all substantive and procedural safeguards recognized in international law on an equal basis with others, and States must provide the necessary accommodations to guarantee due process.

Principle 6 Persons with disabilities have the right to free or affordable legal assistance.

Principle 7 Persons with disabilities have the right to participate in the administration of justice on an equal basis with others.

Principle 8 Persons with disabilities have the rights to report complaints and initiate legal proceedings concerning human rights violations and crimes, have their complaints investigated and be afforded effective remedies.

Principle 9 Effective and robust monitoring mechanisms play a critical role in supporting access to justice for persons with disabilities.

Principle 10 All those working in the justice system must be provided with awareness-raising and training programmes addressing the rights of persons with disabilities, in particular in the context of access to justice.

The picture at the top is from the Brisbane Supreme Court showing a large abstract mural behind the Judges’ bench. The picture at the bottom is an attempt to make the defendant dock wheelchair accessible.

Who does the designing and what do they design? If the design works, users don’t think about the designer. But when the design works poorly, or not at all, the designer becomes the focus. “What were they thinking?” is the catch-cry. In spite of much research and literature on designing thoughtfully and inclusively, we still have a long way to go. So who do designers design for?

Who does the designing and what do they design? If the design works, users don’t think about the designer. But when the design works poorly, or not at all, the designer becomes the focus. “What were they thinking?” is the catch-cry. In spite of much research and literature on designing thoughtfully and inclusively, we still have a long way to go. So who do designers design for? Who thought of kerb cuts in the footpath? 30 years ago policy makers couldn’t understand why anyone needed kerb cuts in footpaths. “Why would anyone need kerb cuts – we never see people with disability on the streets”. This is part of the

Who thought of kerb cuts in the footpath? 30 years ago policy makers couldn’t understand why anyone needed kerb cuts in footpaths. “Why would anyone need kerb cuts – we never see people with disability on the streets”. This is part of the  Access Easy English has

Access Easy English has  “Inclusion” is a word used widely, but what do we mean by this? How does it happen? Who makes it happen? Given that we are not inclusive now, it has to be a futuristic concept – something we are striving for. If we had achieved it we would be talking about inclusiveness, and we wouldn’t be writing policies and advocating for it.

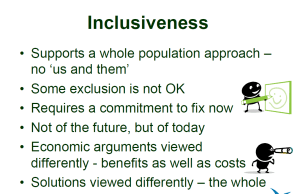

“Inclusion” is a word used widely, but what do we mean by this? How does it happen? Who makes it happen? Given that we are not inclusive now, it has to be a futuristic concept – something we are striving for. If we had achieved it we would be talking about inclusiveness, and we wouldn’t be writing policies and advocating for it. A conference paper

A conference paper supports a whole population approach. Economic arguments and solutions are viewed differently. Inclusiveness is not a contest of rights and not one group giving something to others. All costs and benefits are measured from this perspective.

supports a whole population approach. Economic arguments and solutions are viewed differently. Inclusiveness is not a contest of rights and not one group giving something to others. All costs and benefits are measured from this perspective.  Universal design isn’t just or only about disability. But it does have a major role to play in improving the lives of people with disability. The

Universal design isn’t just or only about disability. But it does have a major role to play in improving the lives of people with disability. The  Supporting concepts of inclusion is one thing; putting it into practice is another. “

Supporting concepts of inclusion is one thing; putting it into practice is another. “ The

The  Confusion still reigns about the international symbol of access (ISA). Is it exclusively for wheelchair users? Or does it denote access for everyone? The ISA was originally created to denote physical spaces for wheelchair accessibility. The access symbol’s meaning has evolved into something much more complex.

Confusion still reigns about the international symbol of access (ISA). Is it exclusively for wheelchair users? Or does it denote access for everyone? The ISA was originally created to denote physical spaces for wheelchair accessibility. The access symbol’s meaning has evolved into something much more complex.  and spaces and eliminating the need to symbolically represent population-based accessibility. Initiatives such as Design for All (DfA) in Europe, which was adopted in the EIDD Stockholm Declaration of 2004, and the Barrier-Free Accessibility (BFA) program in Singapore, promote a social model of disability by encouraging barrier-free design of products, services, and environments for people of all abilities and under varying socioeconomic situations.”

and spaces and eliminating the need to symbolically represent population-based accessibility. Initiatives such as Design for All (DfA) in Europe, which was adopted in the EIDD Stockholm Declaration of 2004, and the Barrier-Free Accessibility (BFA) program in Singapore, promote a social model of disability by encouraging barrier-free design of products, services, and environments for people of all abilities and under varying socioeconomic situations.”